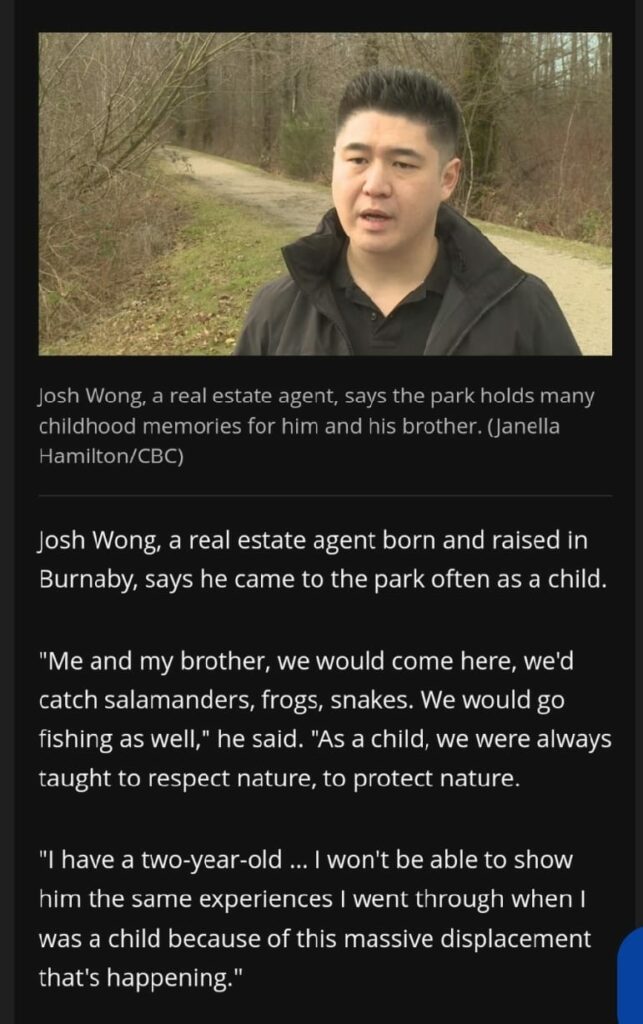

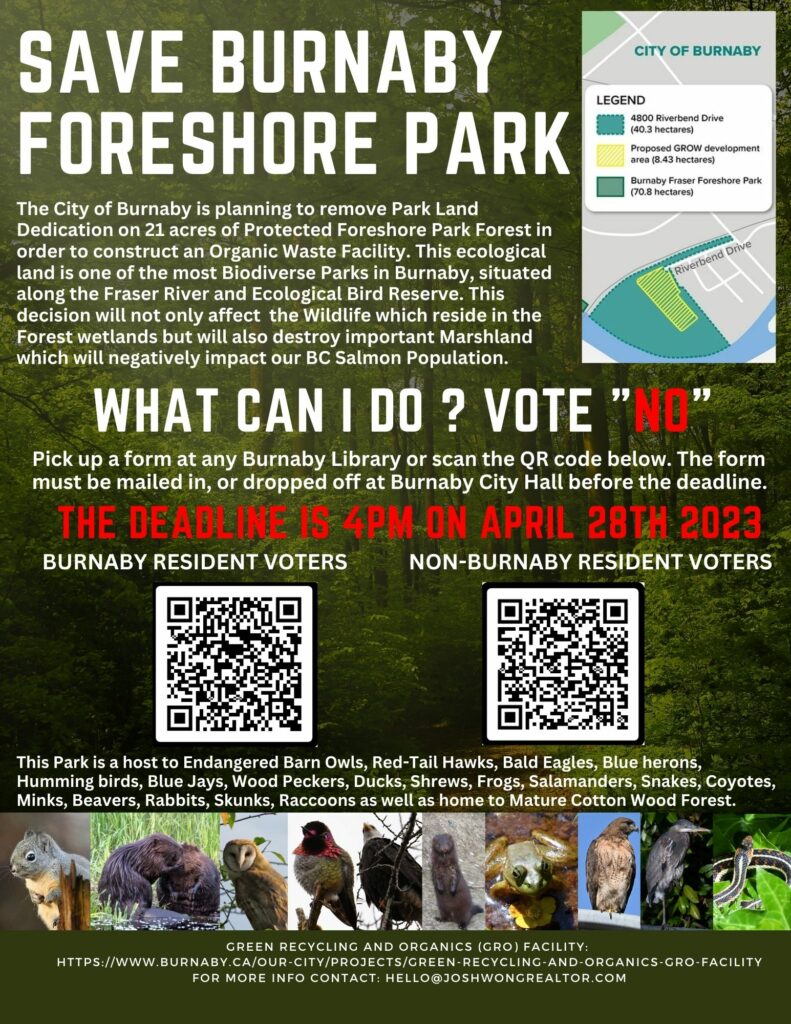

We came together as a community to voice our concerns to the City of Burnaby in an effort to challenge the construction of a 21 acre organic waste facility being constructed on dedicated park land (Fraser Foreshore Park).

This effort paid off today, all thanks to fellow residents who went out of their way to rally and volunteer by putting up flyers, handing out ballots, door-knocking their neighbourhoods and sending emails to the Burnaby council members. We spoke with as many media outlets as possible, we wanted our voices heard. We created awareness in every possible way, we bridged different generations and communities in a consolidated effort. We worked with groups who had created dedicated websites for this initiative, we worked with environmental groups and NGOs. But more importantly, it was the sheer passion of a community that came together to give a voice to the biodiversity and animals which reside at Fraser Foreshore Park. This landmark decision will set the precedent for future generations.

There is no power for change greater than a community discovering what it cares about. And this is the perfect example of what a community can accomplish when we work together.

We also want to thank Burnaby’s Mayor Mike Hurley and Burnaby Council members for hearing us out and reconsidering their decision. We hope your compassion and the considerations we witnessed today, ring true for all future projects which will take place in the City of Burnaby

We also want to thank Burnaby’s Mayor Mike Hurley and Burnaby Council members for hearing us out and reconsidering their decision. We hope your compassion and the considerations we witnessed today, ring true for all future projects which will take place in the City of Burnaby

The Situation

The City of Burnaby currently spends $3.6 million per year to have its greenwaste processed at a private facility in Delta (20-30km away), plus the cost and other impacts of trucking it there. As with everything lately, the cost of this contract has risen dramatically, doubling since 2019. The city proposed building a Green Recycling Organic Waste (GROW) facility to eliminate this expense, lessen environmental impact and generate revenue.

The GRO facility, expected to cost $182 million, would move the processing in-house and take those trucks off the road. With a proposed footprint of 8.5 hectares, up to 150,000 tonnes of organic waste would be recycled annually into high quality soil and the methane byproduct sold to heat 5,000 homes, supplementing the natural gas already in use.

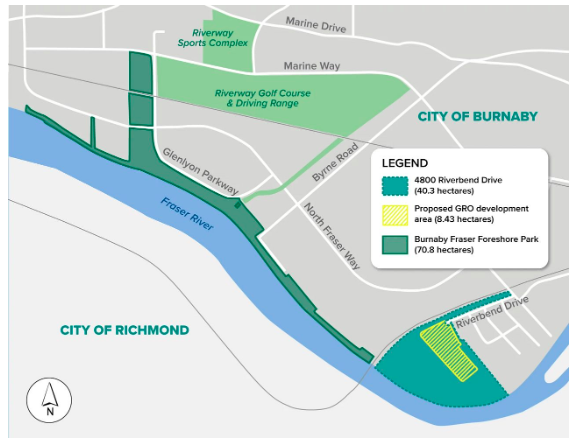

Trouble is, the City of Burnaby determined that the most suitable location for the facility was Burnaby Fraser Foreshore Park, an area the city had already designated as a critically important wetland ecological reserve. Local residents sought support to oppose, above all else, the location chosen for the GROW Facility and the BC Chapter of BHA enthusiastically offered our platform to the cause. The people spoke, and on March 20 the council decided to continue its search for a suitable location.

Source: City of Burnaby

Why there?

Two main factors went into this decision. According to Mayor Mike Hurley, other locations considered were either too small or too close to a protected stream. Perhaps the Fraser, the longest river in BC and a vital waterway through the Lower Mainland, isn’t offered the same protection. Nevertheless, the intention was to place the facility as far back from the river as possible.

The second pertains to what is already there. Metro Vancouver operates a Waste-to-Energy Facility (WEF), incinerating 260,000 tonnes of post-recycled waste (25% of that produced in the region) and generating enough electricity to power 16,000 homes. Metro Vancouver claims to earn $8 million from selling this electricity and $300,000 from selling the 5,000 tonnes of metal recovered to a company that produces reinforcing steel. The WEF exists in the industrial park immediately adjacent to the Fraser Foreshore park, and the city intended to establish the area as a ‘Green Energy Centre’ with the District Energy Utility yet to be built. With the potential revenue generated and the positive environmental outcomes of each facility, the plan has some legs.

It’s not a bad idea, but…

There’s always more to the story. The question remains how beneficial it would be to place these facilities together at all, even without the destruction of protected parkland. One guiding principle of urban design is that the greenest building is one that already exists, owing to the fact that demolition and construction are high overheads to pay off, both financially and environmentally. With nature running the project, and the time required to establish such an ecosystem, the full replacement cost runs very high.

Also consider the (very simple) financials that spending $180 million to save $3.6 million, plus unofficial revenue estimates of $1.8 million, is a 3% return on investment; one could argue that investing the money at a 5% return and continuing business as usual would save this vital ecosystem and generate an additional $3.6 million for the city as a bonus. Of course, this is absolutely an oversimplification.

The Moral

The consensus seems to be that the community generally supports the facility, but unanimously opposes the location. This did not appear to be a difficult decision. And it brings to light the issue of destroying nature to save nature. The City of Burnaby proposed to build “salmon-supporting tidal creeks” and relocate the owls that live in the area but this misses the mark. In ‘What We Owe The Future’, William MacAskill implores that we must consider the permanent effect of our decisions, and even considering the best intentions and outcomes of a facility such as GROW, the ecosystem and wildlife destroyed can not be replaced.

It’s encouraging that projects to invest in the circular economy and improve our waste management are receiving support, but it can’t come at the expense of irreplaceable natural areas. The issue here was, as the maxim goes, location, location, location. Solutions such as the GROW facility have the potential to offer substantial positive environmental results, even if some of the details require ironing out.